A Retrospective Analysis Exploring the Impact of Psychiatric Comorbidities on the Time to Initiate HIV Treatment

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.5195/ijms.2025.3380Keywords:

HIV, Psychiatry, Antiretroviral therapy (ART), Depressive Disorder, Major, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Schizophrenia, Mental Health, Anxiety Disorder, Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation, Psychiatric ComorbiditiesAbstract

Background: Timely initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) is critical for optimal HIV management. However, psychiatric comorbidities may influence treatment adherence, healthcare engagement, and overall outcomes. This retrospective cohort study explored the impact of major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and schizophrenia on the time to initiation of ART for HIV management.

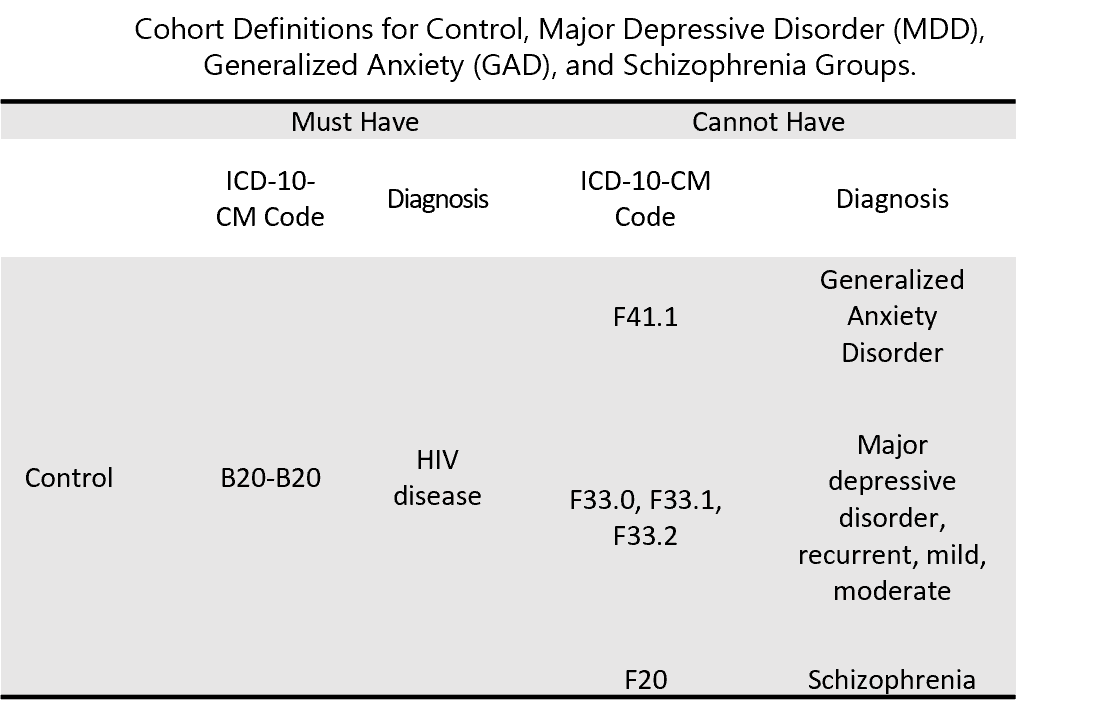

Methods: Using TriNetX, a de-identified database encompassing 66 U.S. healthcare organizations, adults aged 18 and older with an HIV diagnosis were identified through insurance billing codes. Participants were categorized into four groups based on psychiatric history: MDD, GAD, schizophrenia, or no psychiatric diagnosis. Each psychiatric group was propensity score–matched to a control group without a prior psychiatric history to minimize bias. Measures of association and Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted to assess time to ART initiation.

Results: There was an observed association between having a psychiatric diagnosis prior to acquiring HIV and a higher likelihood of initiating ART, compared to controls. Additionally, those with a psychiatric diagnosis were observed to have initiated ART sooner. The median time to ART initiation was 136 days for MDD, 129 days for GAD, and 163 days for schizophrenia, compared to 312, 229, and 302 days in their respective control groups.

Conclusion: Individuals with psychiatric comorbidities were more likely to begin ART earlier than those without a psychiatric condition. This may reflect increased healthcare engagement among patients with established psychiatric care, highlighting the importance of integrated behavioral and medical health services for improving HIV treatment outcomes.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fast facts: HIV in the US by age [Internet]. 2024 Nov 14 [cited 2025 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/data-research/facts-stats/age.html

2. Radix AE, Fine SM, Vail RM, et al. Rapid ART initiation [Internet]. Johns Hopkins University; 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557123/

3. Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Sharma S, et al. Long-term benefits from early antiretroviral therapy initiation in HIV infection. NEJM Evid. 2023;2(3):evidoa2200302.

4. Lewden C, Chêne G, Morlat P, et al. HIV-infected adults with a CD4 cell count greater than 500 cells/mm³ on long-term combination antiretroviral therapy reach the same mortality rates as the general population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(1):72–7.

5. Uy J, Armon C, Buchacz K, Wood K, Brooks JT, HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. Initiation of HAART at higher CD4 cell counts is associated with a lower frequency of antiretroviral drug resistance mutations at virologic failure. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(4):450–7.

6. Bouabida K, Chaves BG, Anane E. Challenges and barriers to HIV care engagement and care cascade: viewpoint. Front Reprod Health. 2023;5:1201087.

7. Mandlate FM, Greene MC, Pereira LF, et al. Association between mental disorders and adherence to antiretroviral treatment in health facilities in two Mozambican provinces in 2018: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):274.

8. Truong M, Rane MS, Govere S, et al. Depression and anxiety as barriers to ART initiation, retention in care, and treatment outcomes in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;31:100621.

9. Grinsztejn B, Hosseinipour MC, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Effects of early versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral treatment on clinical outcomes of HIV-1 infection: results from the phase 3 HPTN 052 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):281–90.

10. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV [Internet]. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services; 2024 [cited 2025 Dec 5]. Available from: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv

11. Molloy R, Brand G, Munro I, Pope N. Seeing the complete picture: a systematic review of mental health consumer and health professional experiences of diagnostic overshadowing. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(9–10):1662–73.

12. National Institute of Mental Health. Mental illness [Internet]. 2024 Sep [cited 2025 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness

13. Sorsdahl K, Petersen I, Myers B, Zingela Z, Lund C, van der Westhuizen C. A reflection of the current status of the mental healthcare system in South Africa. SSM Ment Health. 2023;4:100247.

14. Moraska AR, Chamberlain AM, Shah ND, et al. Depression, healthcare utilization, and death in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):387–94.

15. Roberts L, Roalfe A, Wilson S, Lester H. Physical health care of patients with schizophrenia in primary care: a comparative study. Fam Pract. 2007;24(1):34–40.

16. Bond GR, Drake RE. The critical ingredients of assertive community treatment. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):240–2.

17. Marshall M, Lockwood A. Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001089. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(4):CD001089.

18. Henwood BF, Siantz E, Hrouda DR, Innes-Gomberg D, Gilmer TP. Integrated primary care in assertive community treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):133–5.

19. Viron MJ, Stern TA. The impact of serious mental illness on health and healthcare. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(6):458–65.

20. Cook BL, Doksum T, Chen CN, Carle A, Alegría M. The role of provider supply and organization in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:102–9.

21. Fleury MJ, Grenier G, Bamvita JM, Perreault M, Jean-Caron L. Typology of adults diagnosed with mental disorders based on socio-demographics and clinical and service use characteristics. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:67.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Lorenzo Guani, Andrew Murdock, Angelica Arshoun, Corbin Pagano, Eduardo Espiridion

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- The Author retains copyright in the Work, where the term “Work” shall include all digital objects that may result in subsequent electronic publication or distribution.

- Upon acceptance of the Work, the author shall grant to the Publisher the right of first publication of the Work.

- The Author shall grant to the Publisher and its agents the nonexclusive perpetual right and license to publish, archive, and make accessible the Work in whole or in part in all forms of media now or hereafter known under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License or its equivalent, which, for the avoidance of doubt, allows others to copy, distribute, and transmit the Work under the following conditions:

- Attribution—other users must attribute the Work in the manner specified by the author as indicated on the journal Web site; with the understanding that the above condition can be waived with permission from the Author and that where the Work or any of its elements is in the public domain under applicable law, that status is in no way affected by the license.

- The Author is able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the nonexclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the Work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), as long as there is provided in the document an acknowledgment of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post online a prepublication manuscript (but not the Publisher’s final formatted PDF version of the Work) in institutional repositories or on their Websites prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work. Any such posting made before acceptance and publication of the Work shall be updated upon publication to include a reference to the Publisher-assigned DOI (Digital Object Identifier) and a link to the online abstract for the final published Work in the Journal.

- Upon Publisher’s request, the Author agrees to furnish promptly to Publisher, at the Author’s own expense, written evidence of the permissions, licenses, and consents for use of third-party material included within the Work, except as determined by Publisher to be covered by the principles of Fair Use.

- The Author represents and warrants that:

- the Work is the Author’s original work;

- the Author has not transferred, and will not transfer, exclusive rights in the Work to any third party;

- the Work is not pending review or under consideration by another publisher;

- the Work has not previously been published;

- the Work contains no misrepresentation or infringement of the Work or property of other authors or third parties; and

- the Work contains no libel, invasion of privacy, or other unlawful matter.

- The Author agrees to indemnify and hold Publisher harmless from the Author’s breach of the representations and warranties contained in Paragraph 6 above, as well as any claim or proceeding relating to Publisher’s use and publication of any content contained in the Work, including third-party content.

Enforcement of copyright

The IJMS takes the protection of copyright very seriously.

If the IJMS discovers that you have used its copyright materials in contravention of the license above, the IJMS may bring legal proceedings against you seeking reparation and an injunction to stop you using those materials. You could also be ordered to pay legal costs.

If you become aware of any use of the IJMS' copyright materials that contravenes or may contravene the license above, please report this by email to contact@ijms.org

Infringing material

If you become aware of any material on the website that you believe infringes your or any other person's copyright, please report this by email to contact@ijms.org